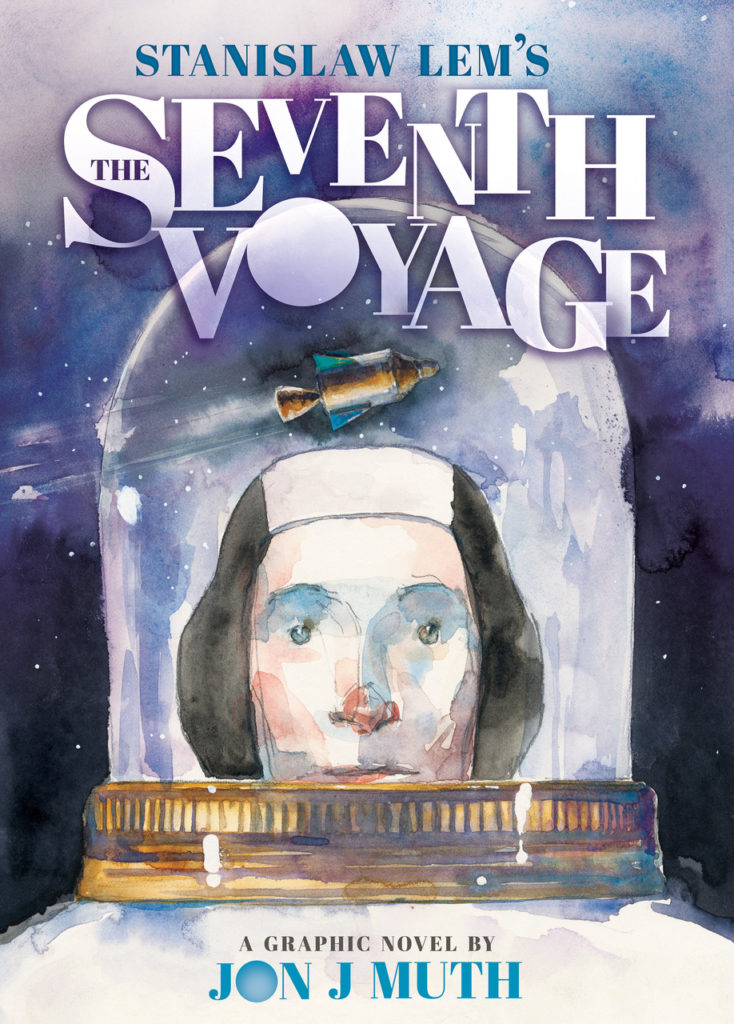

We are thrilled, as Jon J Muth is a renowned author of graphic novels and the recipient of many awards. His work based on one of Tolstoy’s stories was called “quietly life-changing” by the New York Times Book Review.

Delicately washed panel artwork by Caldecott Honoree Muth (Zen Shorts) underscores the hilarity of late Polish author Lem’s short story, originally published in 1957. Unable to repair his spaceship’s rudder alone, astronaut Ijon Tichy enjoys a “modest supper,” works some calculations, and heads to bed. (Readers will note with amusement the spacecraft’s cozy domestic fixtures: striped pajamas and pink oven mitts, an overstuffed armchair and fully equipped kitchen.) He’s awakened by another astronaut (“We’re going out and screwing on the rudder bolts”), but as there is no other astronaut—Tichy is the only one aboard—he dismisses the second as a phantom. Slowly the situation becomes clear: Tichy has entered a time loop, and the other astronaut is Tichy himself, as he exists 24 hours in the future. Lem follows the idea into absurdity as the Tichys multiply (“I saw my Monday self staring at me… while Tuesday me fried an omelet”), then descend into slapstick chaos, beginning to “quarrel, argue, bicker, and debate.” Though the multiple iterations may feel chaotic for some, Kandel’s translation and Muth’s art imbue the original with a crystalline, humorous clarity and delight. Ages 8–12. (Oct.) https://www.publishersweekly.com/9780545004626

Stanislaw Lem, illus. by Jon J Muth, trans. from the Polish by Michael Kandel. Graphix, $19.99 (80p) ISBN 978-0-545-00462-6

It has been said, and with much justice, that Stanislaw Lem has transformed science fiction from a genre to a literature.

It has been said, and with much justice, that Stanislaw Lem has transformed science fiction from a genre to a literature.  His current collection of short stories, essays and obiter dicta bear out this high characterization because it shows that Lem has lost none of his inventive powers, ironical musings, corruscating wit and narrative skills. The concept of Imaginary Magnitude is itself thought provoking: In the next century people will be too busy to read books from cover to cover. Accordingly Lem provides us with the prefaces to important volumes.

His current collection of short stories, essays and obiter dicta bear out this high characterization because it shows that Lem has lost none of his inventive powers, ironical musings, corruscating wit and narrative skills. The concept of Imaginary Magnitude is itself thought provoking: In the next century people will be too busy to read books from cover to cover. Accordingly Lem provides us with the prefaces to important volumes.  “Provocation” is probably one of the most important of Lem’s essays, unfortunately never translated into English. It is a review of a non-existent book about the Holocaust. The review was so suggestive that one of the members of the Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland had publicly claimed to have this non-existent book in his library.

“Provocation” is probably one of the most important of Lem’s essays, unfortunately never translated into English. It is a review of a non-existent book about the Holocaust. The review was so suggestive that one of the members of the Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland had publicly claimed to have this non-existent book in his library.