In my childhood my father showered me in toys. And there might not have been anything strange about that, if it weren’t for the fact that he had already been buying toys for many years before I was born. On a trip to Russia in the 1960s, for example, he bought a model aeroplane, assembled it in his hotel room, but then found he couldn’t get it out of the room because of its huge dimensions, so he instantly presented it to a writer friend with whom he was sharing the room, and who was going to stay on in Moscow a little longer. When I grew up he complained that his son didn’t want to play with the toys he bought any more. From then on he bought far fewer of them, but whenever he came across a particularly beautiful model of a ship or a steam engine, he couldn’t stop himself.

In my childhood my father showered me in toys. And there might not have been anything strange about that, if it weren’t for the fact that he had already been buying toys for many years before I was born. On a trip to Russia in the 1960s, for example, he bought a model aeroplane, assembled it in his hotel room, but then found he couldn’t get it out of the room because of its huge dimensions, so he instantly presented it to a writer friend with whom he was sharing the room, and who was going to stay on in Moscow a little longer. When I grew up he complained that his son didn’t want to play with the toys he bought any more. From then on he bought far fewer of them, but whenever he came across a particularly beautiful model of a ship or a steam engine, he couldn’t stop himself.

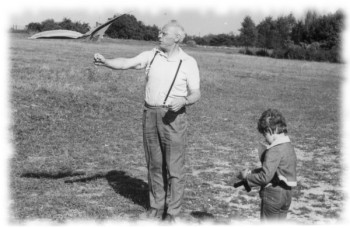

Whenever I paid my father a visit, I always began with the sacramental question: “Have you got time, Dad?” For me he usually had. We had an interest in geophysics – my father used to draw volcanoes, we looked at anatomy or astronomy books together, and there was a lot of talk about the planets, whose names I was able to recite before I started school. My father did not criticise my suggestion that the rings of Saturn are turning more and more slowly, although keeping silent in response to a view that so blasphemously violated the fundamental laws of mechanics must have cost him a lot. Specially for my use he designed a vehicle powered by dogs and cats (instead of an engine). His more advanced model was equipped with an extra dog and cat for reverse gear. Naturally, both vehicles remained at the drawing-board stage, whereas the measure of his devotion to his son was a crankshaft-propelled model of the railway up Kasprowy mountain that he designed, and which for some time ran diagonally across his study between the bedside table and the bookshelf, almost immediately above his desk.

Sharing out his sweets – chocolate-coated marzipan, which my father called “marzipan bread” – had its own special ritual. My father would open the cupboard, take out a pair of scissors, wipe the blade on his handkerchief, and then, quiet and focused, he would unwrap a piece of marzipan and cut off two portions – one for me and one for him. After a moment of blissful, contemplative silence, with a brisk sweep of his hand my father would tip the crumbs into the gap under the desk flap – over time quite a lot of them collected in there. These marzipan feasts had a conspiratorial atmosphere because – though it was never mentioned – we were both aware that my mother would not have approved of our way of disposing of the crumbs, and the way the scissors were cleaned could also have prompted doubts.

Sharing out his sweets – chocolate-coated marzipan, which my father called “marzipan bread” – had its own special ritual. My father would open the cupboard, take out a pair of scissors, wipe the blade on his handkerchief, and then, quiet and focused, he would unwrap a piece of marzipan and cut off two portions – one for me and one for him. After a moment of blissful, contemplative silence, with a brisk sweep of his hand my father would tip the crumbs into the gap under the desk flap – over time quite a lot of them collected in there. These marzipan feasts had a conspiratorial atmosphere because – though it was never mentioned – we were both aware that my mother would not have approved of our way of disposing of the crumbs, and the way the scissors were cleaned could also have prompted doubts.

Among my father’s construction successes I should include the hand-made electric engine, complete with coil; to wind it up he built a special, crank-driven mechanism. As far as a seven-year-old’s safety was concerned, it wasn’t the ideal construction. The engine really did work, yet many of its exposed parts had 110 volts of live electricity running through them. As a dutiful chronicler I should add that from the initial stage of building this engine, my father was so absorbed in his creative construction work that he forgot all about my presence.

As a small boy I often kept my father company while he performed his morning toilet. As he shaved with an electric Remington, a scent of Old Spice Pre-Electric cologne filled the air, and so did various pieces of music. Despite the declarations he used to make in interviews that he was “deaf as a post”, he not only often sang, but he liked serious music, especially Beethoven’s symphonies, jazz – particularly duets with Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald, and the “Old Men’s Cabaret” (singing a song called I’ll Swallow You) – and also some of the songs from the Beatles film, Yellow Submarine.

The repertoire he used to sing while shaving included some funny Ukrainian ballads – there was one about a girl who spat at her beloved because he didn’t look at her the right way, another about a lover who didn’t catch cholera, although it struck down the entire village, and one about another girl who dug her beloved up from his grave to give him a proper scrubbing before burying him again. The tune for the song about cleaning up the dead chap was surprisingly jaunty and jolly.

Soviet songs, such as “I know not of any other land where man can breathe so freely”, supplemented songs from Lvov, sung in a gentle baritone, with a Lvov accent. …

Another highly rated song was a comic ditty about Makary (“There once was a peasant Makary, He was incredibly greedy”), who refused to help a poor widow and her child and burst from overeating. My father used to perform this piece with great gusto, often punctuated by laughter.

In the song about the Uhlans, without interrupting his shaving, he used to sing the girl’s part, “If he thinks I’m sweet, I shan’t put up a fight, Let him take me, take me”, in a soprano voice.

The morning favourites also included a song about Miss Franciszka who, along with the candidate rejected as her suitor by his would-be parents-in-law, committed suicide, by means of a sausage “laced with strychnine”, of which there must have been plenty to hand because the girl’s father was a butcher.

The French and English songs seemed to be straight from the jazz canon. For a long time I was convinced these were “standards” of the 1950s and 1960s, which for unknown reasons were never played on the radio. But in fact at least one of those tunes was probably my father’s own composition to the words of Robert Burns’ poem, “A Fond Kiss”. …

After his morning toilet-cum-concert, we sometimes played with an artificial fly with a hidden metal plate inside; you put it on a sheet of paper and brought it to life by holding a magnet under it. You could also scatter iron filings on the paper and watch them “come to life” when you put the magnet underneath, or examine the lines of the magnetic field affected by a longer magnetic bar. Almost every day we checked with a compass to see if north was where it had been the day before, and then we verified the result with the help of another compass. Once cleared of all his manuscripts and books, the green cloth on his desk was ideal for a game of tiddlywinks, which didn’t involve just ordinary playing, but tactically complicated military operations, demanding an ingenious strategy.

published by the courtesy of The Book Institute