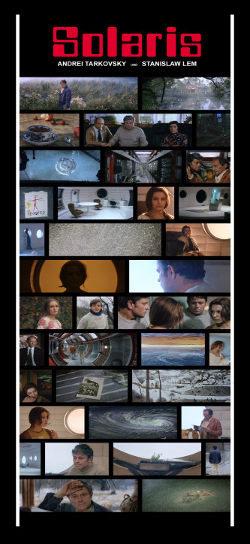

SOLARIS by Tarkovsky

1972 Soviet Union

1972 Soviet Union

Drama/Science-Fiction

Run-time: 166 min

Directed by: Andrei Tarkovsky

Screenplay: Fridrikh Gorenshtein

Based on: Stanislaw Lem's novel

CAST

Chris Kelvin: Donatas Banionis

Harey: Natalya Bondarchuk

Henri Berton: Vladislav Dvorzhetsky

Snaut: Jüri Järvet

Gibarian: Sos Sargsyanr

Produced by Viacheslav Tarasov

Original Music by Eduard Artemyev

Cinematography by Vadim Yusov

Film Editing by Lyudmila Feiginova

Nina Marcus

Awards:

Cannes Film Festival 1972:

FIPRESCI Prize

Grand Prize of the Jury

Nominated: Golden Palm

I have fundamental reservations to this adaptation. First of all I would have liked to see the planet Solaris which the director unfortunately denied me as the film was to be a cinematically subdued work. And secondly — as I told Tarkovsky during one of our quarrels — he didn't make Solaris at all, he made Crime and Punishment. What we get in the film is only how this abominable Kelvin has driven poor Harey to suicide and then he has pangs of conscience which are amplified by her appearance; a strange and incomprehensible appearance. This phenomenalistics [sic] of Harey's subsequent appearances was for me an exemplification of certain concept which can be derived almost from Kant himself. Because there exists the Ding an sich, the Unreachable, the Thing-in-Itself, the Other Side which cannot be penetrated. But in my prose this was made apparent and orchestrated completely differently... I have to make it clear, however, that I haven't seen the whole film except for 20 minutes of the second part although I know the screenplay very well because Russians have a custom of making an extra copy for the author.

My decision to make a screen adaptation of Stanisław Lem's Solaris was not a result of my interest in science fiction. The essential reason was that in Solaris Lem undertook a moral problem I can closely relate to. The deeper meaning of Lem's novel does not fit within the confines of science fiction. To discuss only the literary form is to limit the problem. This is a novel not only about the clash between human reason and the Unknown but also about moral conflicts set in motion by new scientific discoveries. It's about new morality arising as a result of those painful experiences we call "the price of progress." For Kelvin that price means having to face directly his own pangs of conscience in a material form. Kelvin does not change the principles of his conduct, he remains himself, which is the source of a tragic dilemma in him.